Pakistan has the second worst gender gap in the world, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report for 2015. The report ranks it 144 out of 145 countries. This gender imbalance is reflected in the country’s financial inclusion numbers, as reported by Pakistan’s 2015 Financial Inclusion Insights (FII) survey.

FII 2015 depicts stark differences between the two genders in the level of financial inclusion, which is defined by access to a full service account. Men are almost twice as likely to be financially included as women (11% vs. 6%). When it comes to digital financial services, merely 0.3% of the sampled women were found to have a mobile money account, compared to 2.1% of men. In comparison, Kenyan mobile money registrations for women is 68% compared to 75% for men.

While financial inclusion generally and digital inclusion specifically has been slow to take off in Pakistan, it has been particularly slow for women due to specific social norms (based on certain interpretations of Islamic scriptures) that create segregation between the sexes. While there are exceptions, arguably, for a majority these norms limit interaction between genders except for that between certain close relations. It becomes more difficult for women to act as customers, as it requires interaction with unrelated men given that most jobs are dominated by men.

Opening a bank account, therefore, becomes an issue for some women, as the bank tellers are likely to be men and registration as well as operation requires interaction with such unrelated men. This effectively creates a culture where men engage with all institutions and conduct transactions outside the home, while women are restricted to home-based activities.

When it comes to mobile money, which theoretically can sidestep these restrictions, there are still several important obstacles:

- Male agents predominate in Pakistan. Mobile money enables registration and payment processes to be conducted in the privacy of one’s own home. But cash-in-cash-out requirements necessitate some level of interaction with agents, almost 100% of whom are male. Nonetheless, when compared with regular banks, the interaction with mobile money agents is limited because other functions such as person-to-person (P2P) transfers and bill payment do not necessitate a visit to an agent.

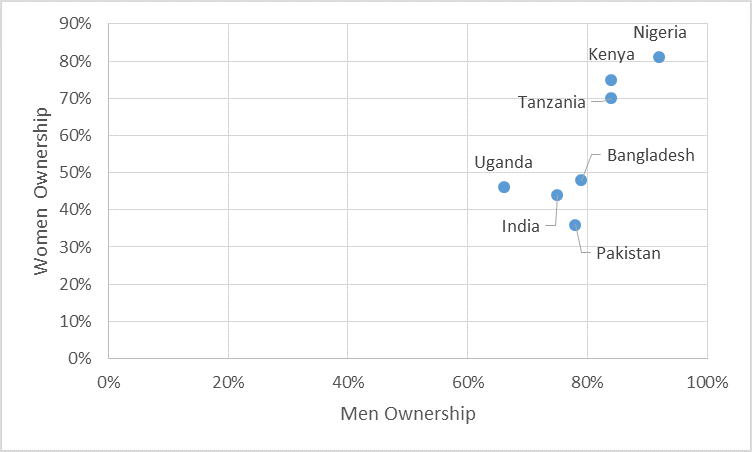

- Few women own phones. In a report by GSMA, it was noted that South Asia has the largest gender gap in mobile ownership. FII 2015 data bolsters these conclusions as depicted below. South Asian countries generally and Pakistan specifically stand out as having the lowest sampled female ownership of mobile phones relative to men.

The Gender Gap in Mobile Phone Ownership

Women in Pakistan have been killed for merely owning mobile phones. These incidents might indicate that, for many male kin, interactions of their female relatives with unrelated men over mobile phones are also a source of “dishonor.” And the impact of such beliefs seem to be significant, as 18% of women non-users in Pakistan responded that they did not use a phone because they were “not allowed to use by family.” For Bangladesh, 3% of women non-users reported the same response, while for India 5% responded that way.

Apart from permission to use mobile phones, women in South Asia seem to rely on friends and family to buy the phones. As the figure below shows, a much lower percentage of women have bought mobile phones themselves in comparison to men. Within South Asia, Pakistan is found to have the lowest proportion of women who buy their own phones.

Addressing the stigma

One way to address these restrictions would be to encourage women entrepreneurs to become mobile money agents. Female retail shop owners, beauty parlor owners, seamstresses, and others like them are ideally suited for female mobile money users, as such entrepreneurs have fixed business addresses and are frequented predominantly by women. One example of such women-focused financial inclusion efforts in Pakistan are carried out by the Kashf Foundation. Since 1999, Kashf has done a cumulative disbursement of more than $400 million in credit to 2.73 million female clients.

Another way would be to counter the stigma through advocacy efforts. These could include gender sensitization through mobile money ad campaigns, public service messages from the Pakistan government, as well as advocacy by donors and NGOs. One crucial ally in that regard could be the clergy in Pakistan. As is seen in the advocacy campaign for polio vaccination of children, the stigma of polio vaccination being “un-Islamic” is countered with the clergy’s help. The same could be done for fighting the stigma associated with female ownership of mobile phone.

The promise of mobile phones is immense for financial inclusion of women. With low registration requirements as well as low logistical demands for operations, digital financial services are ideally suited for the unbanked women in Pakistan. However, the social norms around gender segregation need to be addressed, including in particular the stigma attached with women’s ownership of mobile phones and their interaction with male agents. This requires a change in mindset and bringing that about is beyond the means and mandate of Pakistan’s mobile money industry. Government, donors, NGOs, and civil society need to come together as the rewards of higher financial inclusion of women have far reaching benefits for the economy and society as a whole.